BY JANA GERING

I hated writing and thought I was exceptionally bad at it right through Middle School. While I was reading at a college level and burning through hundreds of books per year, writing eluded me. The minute I tried to put a story down on paper, the words ruined it.

Mr. Cheesman taught freshman English, first period. I’m always glad now it was first period. I grew to savor that early-morning quiet where we straggled into the room. There would always be a question on the board, and a half-sheet of recycled printer paper on each desk. This was Daily Journaling, DJs for short. We had to write at least 5 sentences to get full marks. The assignments ranged from simple questions about summer activities to responding to a scenario, to questions of choice or philosophy, or free writing on a given topic, word, sentence, or person. Sometimes they were connected to the stories we were reading.

The rules adjusted as we went along, because Mr. Cheesman actually read and graded those DJs. After the first week, we were not allowed to use the word “that.” For every “that,” we’d lose a full point of the five points each DJ was worth. It was hard at first, to break the habit. But then it was kind of fun to find a workaround every time I wanted to put in a “that”. I’ve never forgotten the rule. Eliminating “that” is still one of the first things I do in an edit run, and it stood me in good stead through all of those University English Literature papers.

I grew to enjoy the rhythm of the Daily Journals, the clarity of the assignment, the extreme limits of time and space and subject. 5 sentences, 10 minutes at most, a slim half sheet of paper. Name, date, done. By the end of the year, writer’s block wasn’t even a thought. I had earned a habit. I walked in, sat in my desk, picked up the pencil and wrote until Mr. Cheesman stopped us.

I still assumed I wasn’t good at writing. But in Mr. Cheesman’s class, I started learning narrative structure and editing, and came to understand how my thoughts were tangled, and getting them out on paper was only the first step.

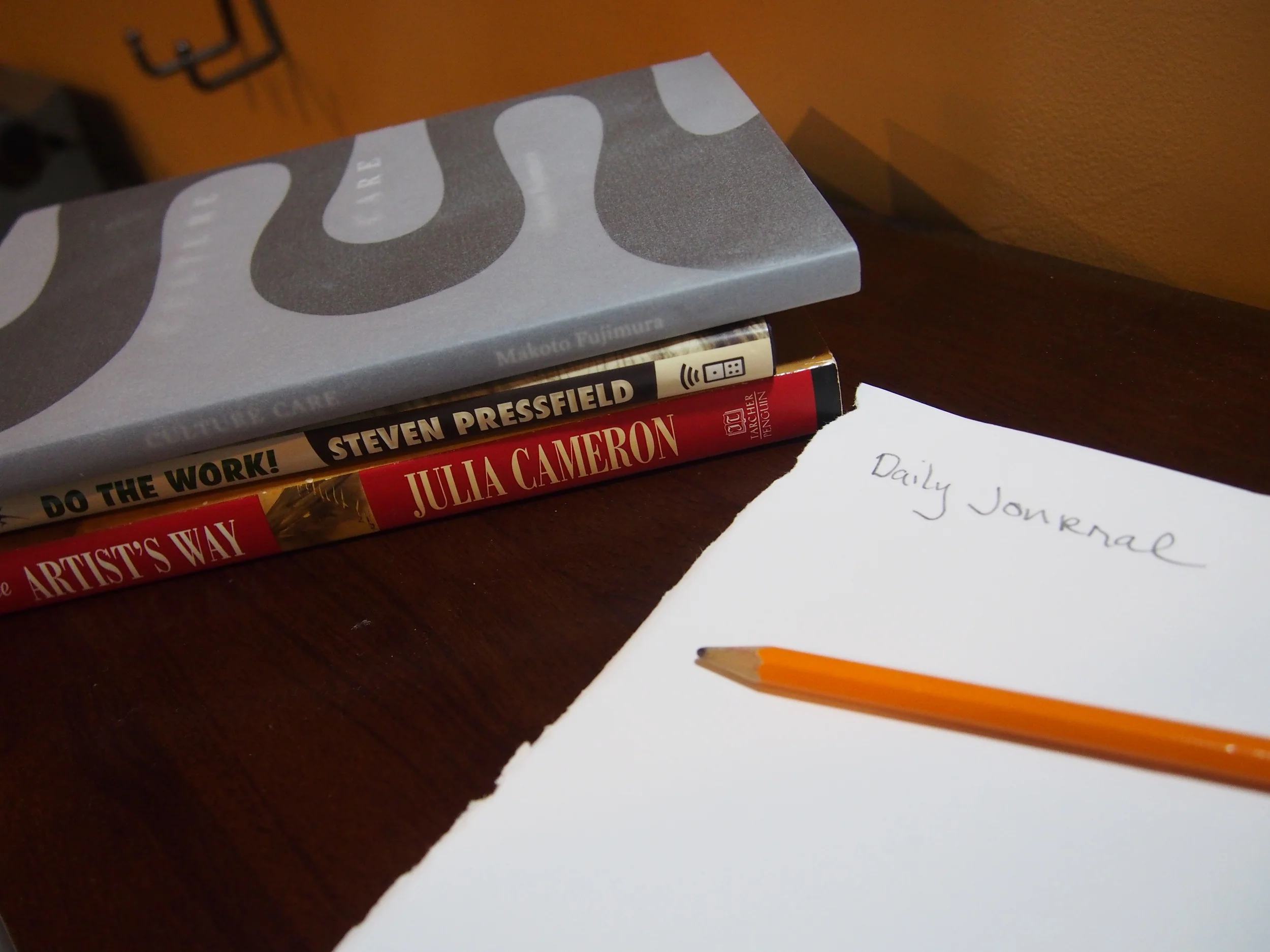

That first period english class taught me in early form what I have since had to painfully re-learn (and sometimes still forget) in Steven Pressfield’s Do the Work, and The War of Art, and in Julia Cameron’s ever-present The Artist’s Way, with its essential “morning pages” practice. Malcom Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule at least gave us a way to understand and quantify the value of practice in our pay-by-the-hour world, and another slim volume called Art & Fear is well marked-up on my shelf.

All of these (very worth-while) books seem to agree that what goes into an artist’s “final product” is just as much time as talent or passion or intellect or voice or vision.

Time. The amount of hours represented by every three-minute pop song played in the top-40 charts alone is astronomical. Even the annoying ones have been written and set to music over days, sometimes months or years, not to mention the time spent playing them over and over again live, recording, producing, and making the music video. And yet saying “I got it for a song” translates to “cheap”. It’s odd that we expect a song to be cheap (or these days, free).

What does your favorite song give to you when you listen, not just when you have it on to drown out noise? Three minutes to be in a different space. Three minutes to learn another perspective, to hear a different way of thinking.

The blog site medium.com (along with other content sites) has started adding a time to each post: ‘4 minute read’ or ‘15 minute read’. It would be interesting to see another metric; ‘3-hour write’ or ‘1-hour write + a knock-down, drag-out fight with an editor that took 4 hours over 2 days and made me cry uncounted tears.’ I don’t tell you when you read this post that it took four pages of writing I didn’t even use, but had to write in order to get here.

This is both an encouraging thought and a discouraging one.

On one hand, it’s encouraging to know that other people struggle with the translation, too. It’s not just you, you know, whatever your medium is. The struggle doesn’t make you a bad writer/painter/musician/copywriter/video game developer.

On the other hand, it would be so much nicer if there was no translation from mind to medium. But maybe we are time-bound creatures for a reason. Time is the only thing we have to give, and the best thing we can receive. Mr. Cheesman gave me 5 minutes a day, and it made me a writer.

Time. To sit for 4 minutes and hear Seattle’s Naomi Wachira is a gift. To spend many minutes staring into the truthful and terrible abyss of Picasso’s Guernica. To go to a movie theater and immerse yourself in a story, without checking your phone. Time is respect. Time is value. Time is relationship. Time is practice.

I’ve mentioned painter Makoto Fujimura in a previous post, and his thoughts on the essential extravagance of Art. In the preface of his new book; Culture Care, he shares about his early marriage, when he was teaching school and making art in the margins of life, and his wife was finishing school:

“As a newlywed couple, my wife and I began our journey with very little...We had a tight budget and often had to ration our food (lots of tuna cans!) just to get through the week. One evening, I sat alone, waiting for Judy to come home to our small apartment, worried about how we are going to afford the rent, to pay for necessities over the weekend. Our refrigerator was empty and I had no cash left. Then Judy walked in with a bouquet of flowers. I got really upset. “How could you think of buying flowers if we can’t even eat!” I remember saying, frustrated. Judy’s reply has been etched in my heart for over thirty years now. “We need to feed our souls, too.”

This is a reminder to me when I have to wake up early, when I get discouraged by the little time I have outside of my day jobs. I need to feed my soul, too. And maybe I should start journaling again.